The shadows grow long as the man makes his way across the plantation.

He moves slowly but with purpose, his dark eyes narrowed under an olive bucket hat. His clothes are simple and drab in colours — earthy-brown trousers and charcoal grey, long-sleeved t-shirt covering his tanned arms. A workman’s attire. From underneath the left sleeve, a long scar pokes out on to the palm of his hand. He is holding a machete. In many ways, he looks like an extra on the set of Narcos. But he’s not. He’s here to do a job.

The ground is coffee-brown and covered in enormous, dry leaves. As the man walks towards his destination, crunching the leaves under his boots, a sputtering propeller plane flies overhead. The whole scene has such a 1990s pulp action flick vibe to it, you’re almost expecting Mel Gibson to stick his head out of the bushes.

He stops in front of a large, green plant, twice his height. Bunches of yellow bananas cover the rolled-up layers of the trunk in clusters. The man lifts up the machete and chops down the plant in a few swift, expert swings. He loads it up on to a crude conveyor belt and the bananas begin their journey with a trip to a warehouse-like building atop a small hill. A few years ago, they would’ve had to be carried by men but these days, the operation is aided by rudimentary but ingenious technology. In the building, they’ll be washed and de-spiderised before being boxed up for the next part of the journey. The bananas are then loaded on refrigerator trucks, driven to the docks, and transferred on to a ship where they will be kept below deck at exactly 13.5°C for the remainder of the trip to prevent them from ripening too quickly. Once ashore in the US, they will be sent to a ripening centre and then distributed to their final destinations. Of the 4.35 million tonnes of bananas imported by the US every year, 66,000 find their way to the US Open in New York.

Tennis’s love affair with the banana dates back to 1960s when Ken Rosewall would occasionally munch on one between games. 20 years later, the image of the fruit in the tennis world was further expanded by Boris Becker who would gobble them up on court with regularity surprising for an athlete from an era when sports diet consisted of gin for breakfast and post-match all-night benders.

In September 1982, Martina Navratilova found herself dejectedly watching her opponent give an on-court winner’s speech. She had just lost a US Open quarterfinal after racing to a quick lead in the match by taking the first set 6-1. But then the wheels suddenly came off and she lost the remaining two sets. Although this was only her second defeat in 70 matches that year, as every professional athlete, she was accustomed to the harsh taste of defeat. This time was different, however. She felt frustrated. “I’m not bitter, but I am most disappointed,” she replied when asked about her post-match emotions.

She was starting to believe that there was an element missing to her game that would allow her to reach full potential. On a friend’s recommendation, she contacted Dr Robert Haas, a sports nutritionist who advised her a change of diet. It cut out all of her favourite foods and instead focused on bland pasta and bananas. Martina wasn’t a fan. “After two days of Haas’s regimen, I was dying,” she remembered. The diet seemed to help, however. Navratilova went on to win 102 of her next 104 matches.

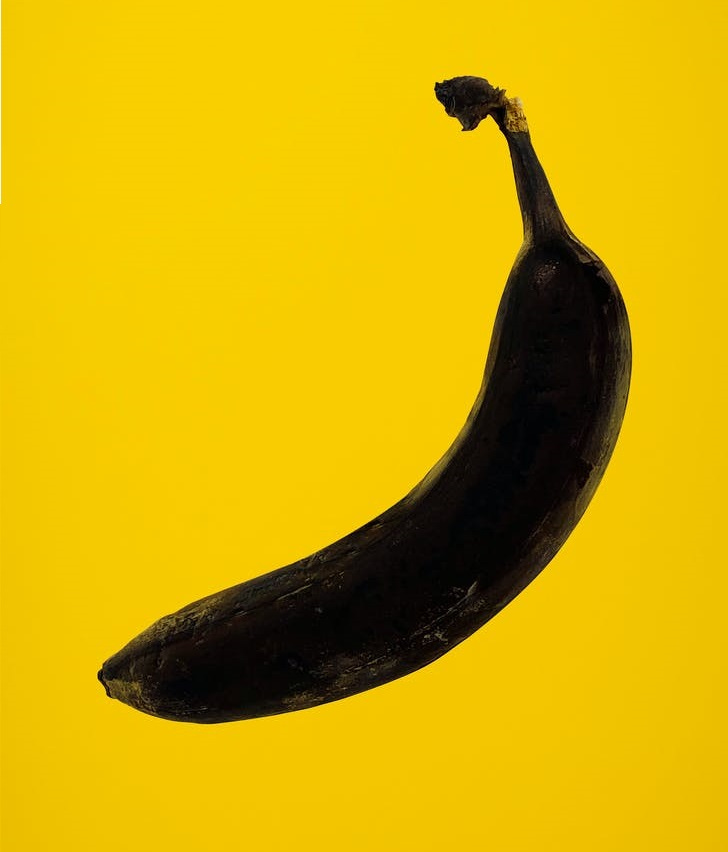

These days the image of tennis players eating bananas between games is nearly ubiquitous. In many ways, it is the perfect fruit. Your regular banana is 111 calories of sucrose, glucose, fructose and a high concentration of potassium, packed in 126g of mushy, easily digestible goodness. It doesn’t weigh you down and provides an almost instant boost of energy which is important when you’re expected to start blasting balls at 130mph 45 seconds after eating.

Still, not every tennis player is a fan. In his 2008 biography, Andy Murray confided that he considers banana “a pathetic fruit”. “They’re not straight and I don’t like the black bit at the bottom,” he went on to say. Still, at the 2013 Australian Open, Andy was seen eating bananas during his marathon victory over Roger Federer. When quizzed, he said that he still dislikes the taste but finds the fruit useful during matches because of 'what they have in them'.

The younger generation, in particular, seems to find the banana a tantalisingly puzzling fruit. Both Denis Shapovalov and Alex De Minaur have been caught on camera struggling to peel one, in case of Shapovalov, going so far as to chuck it onto the ground in frustration.

Earlier this year, in the last qualifying round of the Australian Open, a french player Elliot Benchetrit has found himself in hot water with the umpire over the yellow fruit. During a changeover, he had asked a ballgirl for a banana and then instructed her to peel it for him while he applied cream to his hands. The befuddled girl looked over at the chair umpire questioningly and he quickly told Benchetrit to peel it himself.

But tennis banana dramas date back much earlier than that. In 1998, Félix Mantilla played Thomas Muster at the Masters in Rome. During a changeover, Muster ran up to Mantilla, grabbed the banana out his hand, and ate it. After the match, Mantilla refused to shake Muster’s hand.

During Sharapova’s 2006 US Open win, Maria’s father was seen waving a banana at his daughter in a gentle reminder to keep hydrating and eating. When asked by the reporters why would he brandish a banana during a tennis match, Sharapova snapped. “My life is not about a banana," she said, "And right now, I'm sitting here as a US Open champion, and the last thing I think people need to worry about is a banana."

Brought to the American public in 1876, the banana has captured hearts and souls, and no other area of life has been influenced by its existence more than the world of sports. It has been witness to great victories and bitter defeats, exhilarating triumphs and soul-crushing disasters. Throughout the history of the sport, the banana has had the best seats in the house — it’s seen the most prestigious tennis stadiums, but also the most remote of courts. It is clear that the many benefits of the banana outweigh the anguish it brings. From New York to London, its hold on the sport continues, and the sight of tennis players munching on, struggling with or arguing over a banana is here to stay.